In the second week of June 2025, The Jerusalem Post and many other newspapers reported that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, before bombing nuclear facilities in Iran described Iran’s theocratic government as an ‘evil and oppressive regime’. ‘The time has come for the Iranian people’, he added ‘to unite around its flag and its historic legacy, by standing up for your [Iran’s] freedom from the evil and oppressive regime’. He declared that Israeli’s military operation was ‘… also clearing the path for you [the Iranians] to achieve your freedom.’ In his view Israel’s fight was ‘… against the murderous Islamic regime that oppresses and impoverishes you [Iranians], and that it was ‘… your [Iranian’s ] opportunity to stand up and let your voices be heard.’

More than twenty years earlier President George W. Bush in his State of the Union address on January 29, 2002, argued that ‘Iran aggressively pursues these weapons [of mass destruction] and exports terror, while an unelected few repress the Iranian people's hope for freedom. ... States like these, and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world. The phrase ‘axis of evil’ also included Ba’athist Iraq and North Korea. The address on January 29, 2002 was delivered less than five months after the September 11 attacks in New York and Washington, and a year later followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq by armed forces of the countries of the so-called ‘coalition of the willing.’

Theocratic regime in Iran didn’t hold back and began to call the U.S. as the Great Satan, and Israel the Little Satan. To thwart their power and aggression it created the so-called ‘axis of resistance’.

The two sides employ these metaphors primarily for the consumption of their own people and the people of other like minded countries/states. One of the main objective is to justify their aggression towards each other through regular armed forces or through terrorist, both covert and overt, operations causing deaths of largely innocent civilians often euphemistically described as ‘collateral’ damage.

The indiscriminate killing of people in Gaza that followed the brutal 7 October massacre and kidnapping by Hamas continues as I write this piece. The Israeli Government calls the retaliation as self defence, a battle for its survival. A similar conflict is continuing between Ukraine and Russia, the two erstwhile republics of the, once utopian, Union of the Soviet Republics.

Although attacks and killings are engineered and authorised by states, it’s the people, men and women, often even young boys and girls, do the killing. Most belong to the armed forces, trained, and obliged to follow orders, and thereby kill. Others, equally numerous are terrorists fighting for or in the name of religious and/or ideological beliefs (nationalism, racism, communism, liberalism, democracism etc.). By and large the same ideologies are relied on by various nation states to justify their aggression against each other.

Like most Indians I am cognisant of the long history of violence and armed conflicts between Hindu and Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, and Sikhs and Muslims. The partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan in 1947 resulted in brutal ethnic and religious cleansing of Muslims from India and of Sikhs and Hindus from Pakistan.

The truth is stark: violence begets more violence but we are unwilling to or incapable of ending the cycle of violence not realising that when we kill human beings, we kill all that can be called humane in us. More importantly, with humans we also vanquish animals, plants, soil, air, and water, the natural environment essential for the well-being of future generations.

After we have killed once, the second time it becomes strangely easier.

So why do we decide to fight each other and kill?

I read George Orwell’s essay Shooting an Elephant more than thirty years ago. I was astounded by it, the honesty of Orwell’s (then Eric Blair) confession as a police officer in Colonial Burma, his racism and overt hatred of the ‘yellow faced’ Burmese. But only five years ago I began writing my essay about him, his life in Burma and the elephant he could have shot.

Did he shoot the elephant? I ask in the essay. Was it him or some other colonial police officer who had done it, and Orwell merely appropriated the story for his essay? Or perhaps what he simply wants to tell is that although he had pulled the trigger, the force that had pushed his finger was the collective will of two thousand or so ‘brown faces’ watching him. He was just a puppet in the hands of the crowd and of the imperial government the honour of which he was scared to besmirch. I was simply an instrument, he wants us to believe, a police officer on duty.

The word instrument reminded me of a Sanskrit word nimitta-mātram that I had read in the poem The Bhagavad Gita, and I decided to include a discussion of some of the verses in which the word appears in my essay.

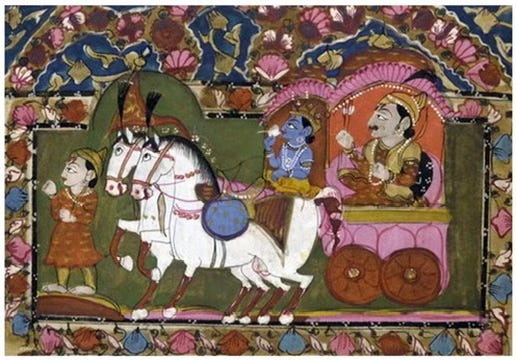

To kill or not to kill is the question that Arjuna, the warrior prince, asks in The Bhagavad Gita. A question to which he hopes Krishna, his friend and charioteer would find a convincing answer otherwise he wouldn’t be able to fight and kill and thereby disgrace himself in the eyes of his gods and his kith and kin.

Most Historians believe that The Bhagavad Gita was a later addition to the Indian epic Mahabharata, which recounts the story of the ‘great war’ between two groups of cousins and their armies that took place sometime around 900 BCE. For centuries, the story was told and retold by professional bards and performers and attained its present form between 200 BCE and 200 CE.

*********************

An Extract from My Essay, George Orwell’s Elephant

On the first day of the eighteen-day war, Arjuna, the chief warrior of the Pandava clan, one of the two groups of cousins, asks Krishna to drive the chariot to the front of the army line so that he can look at his enemies. Krishna obliges but Arjuna soon discovers that the enemies he is going to fight, and kill, are his close and distant relatives, his teachers and mentors, and his friends. Dejected, he lays downs his arms. In the following seventeen dialogues Krishna attempts to persuade Arjuna to fight.

Krishna, however, isn’t an ordinary charioteer; he is also one of the many incarnations of the Hindu god Vishnu. Hence, his conversation with Arjuna turns into an exposition of basic Hindu philosophy and ethics.

Krishna says to Arjuna that he should fight and therefore be ready to kill because ‘the wise do not lament either the dead or the living.’ The wise know that ‘there was never a time when either I, or you, or those rulers of men did not exist. Nor will there ever be a future when all of us cease to exist.’ Whatever takes birth or dies, argues Krishna, is just the body whereas the soul, immortal as it is, remains unharmed. The body is mortal and therefore to grieve for it is neither wise nor beneficial.

Arjuna should fight, says Krishna, because the battle he has been asked to participate in is righteous. His enemies, although they are his cousins and friends, are impure, sinful and corrupt and therefore it is his duty to take up arms against them. Arjuna should fight, says Krishna, because he is a proud Kshatriya, a warrior, and therefore, it is his dharma to take up arms and attack. Krishna urges Arjuna to ‘perform the action prescribed for him, because it’s better to act than to be inactive.’ To fail to act according to one’s code of conduct, argues Krishna, is naturally and morally wrong.

Arjuna should fight, says Krishna, believing that he is acting ‘in the spirit of sacrifice, free from any form of attachment,’ and without ‘an eye on its fruit.’ He shouldn’t worry about winning or losing, living or dying. By keeping himself detached from his action he would be able to set himself ‘free from the good and evil consequences,’ resulting from it.

Arjuna should fight, says Krishna, because it’s what the gods have willed. The fate of his enemies and his own is prearranged. Being evil, his enemies have to die and die they will. Krishna says:

I am Time, the destroyer of the worlds, matured, and occupied now in destroying the world. Even were you not here, all the warriors, standing variously arrayed in different armies, shall be no more. Therefore, arise and obtain glory. Conquering your enemies, enjoy a flourishing kingdom. I myself have already killed these earlier. Become merely the instrument (nimitta-mātram), O Savyasācin [Arjuna].

As expected, Arjuna gives in. Krishna is persuasive; his logic flawless. ‘My ignorance has been destroyed,’ he says to Krishna, ‘and I have got back my memory through your grace O Krishna. I shall be steady, freed of doubt. I shall do what you have stated.’

You have been duped Arjuna, I say. Duped and forsaken. Unfortunately, Arjuna isn’t the first or the only person hoodwinked by sweet talkers who hold the reins of power. We have encountered them too often in history and many more will show up in the future, for the weakness to let ourselves be duped is universal.

We are morally weak, always looking for excuses and scapegoats.

Was Orwell one of them?

Perhaps he was.

*********************

As I read the dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna it becomes clear that he uses three reasons to convince Arjuna to fight and thereby kill: Arjuna’s fight is righteous and his enemies are impure, sinful, and corrupt; Arjuna is a warrior and it is his dharma (duty or code of conduct) to fight; it is the will of god, his divine order, that Arjuna should fight, and therefore turn into god’s instrument, doing his work. Krishna also advises how Arjuna can avoid the feelings of pride or guilt and shame: Arjuna should engage in the battle and kill dispassionately, detached from its outcome; and that he shouldn’t overly grieve for those he had killed, because he has only killed their perishable bodies whereas their souls, like his own, remain beyond the cycle of birth and death.

One of the most famous scientists who quoted verses from The Bhagavad Gita to possibly justify his decision to head the Manhattan Project's secret weapons laboratory, set up to design, test, and create the atomic bomb was J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967). He was aware of its vast destructive power. And it’s quite likely he struggled to explain, if not to others but to himself, the moral consequences of his decision and actions.

According to a profile in the Life magazine published in 1949, after the Trinity Test explosion in July 1945, he had recalled a verse from The Bhagavad Gita:

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one ... Now I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds.

Sixteen years later in an interview he added more information to that quote:

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, The Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

On Youtube one can find several video clips of Oppenheimer uttering these words.

His biographers and other journalists and historians repeatedly mention his knowledge of Sanskrit, The Bhagavad Gita, and other religious and secular works in Sanskrit. My reading of the Sanskrit text and its Hindi and English translation reveals that the above words are a conflation of two separate verses from Chapter 11.

The first lines about the ‘the radiance of a thousand suns …’ comes from the verse 12 of the chapter. In Sanskrit it reads:

दिवि सूर्यसहस्रस्य भवेद्युगपदुत्थिता ।

यदि भा: सदृशी सा स्याद्भासस्तस्य महात्मन: ॥ १२ ॥

It’s English, prose or unlineated, translation by Vrinda Nabar and Shanta Tumkur reads:

Were the radiance of a thousand suns to blaze forth at one go in the sky, It might approximate the magnificence of this exalted being.

In The Bhagavad Gita, these words are not uttered by Krishna/Vishnu or Arjuna but Sanjaya, the bard-narrator who was summoned by the blind King, the father of the Kauravas, and the uncle of the Pandavas, the two waring sides, to bring to him a running commentary or an eye-witness account of the battle. In this verse Sanjaya describes the appearance of Supreme Divine Being that Krishna reveals to Arjuna. In Hinduism Krishna is understood to be a reincarnated deity of Vishnu, who is also one of the many forms or essences of one single Supreme Divine Being. All Hindu deities represent different forms of the divine being.

The words that follow the first few lines come from the verse 32 of the same chapter. The Sanskrit text of the verse reads:

कालोऽस्मि लोकक्षयकृत्प्रवृद्धो

लोकान्समाहर्तुमिह प्रवृत्त: ।

ऋतेऽपि त्वां न भविष्यन्ति सर्वे

येऽवस्थिता: प्रत्यनीकेषु योधा: ॥ ३२ ॥

Vrinda Nabar and Shanta Tumkur translate this verse into English as:

I am Time, the destroyer of words, matured, and occupied now in destroying the world. Even were you not here, all the warriors, standing variously arrayed in different armies, shall be no more.

This verse is not spoken by Sanjaya but by Krishna, a reincarnation of Vishnu.

As an eighteen year old youngster, I was lucky to learn Sanskrit in the High School, and had read The Bhagavad Gita several times. Then I was able to recite many verses from memory but as it often happens, I frequently would mistakenly mix and fuse different verses. Maybe that’s what had happened with Oppenheimer as he was witnessing the giant plume of radiant fire rising into the sky. Was he awe-stricken? Perhaps he was. But he could also have been a little chastened, even apprehensive of the enormous destructive potential of the device as a weapon of war. As a scientist he was proud of the achievement of his team but as a human being he was uncertain about the moral implications of their creation.

Maybe this could be the reason that two days before the July 1945 Trinity test he recalled words of another Sanskrit verse. Generally, this verse is also described to be sourced from Oppenheimer’s favourite The Bhagavad Gita but it comes from a different source: from the section Nītiśataka of the book Śatakatraya by Bhartṛhari, a 5th century CE, poet, linguist, and philosopher.

Oppenheimer is reported to have quoted the verse in English as:

In battle, in forest, at the precipice of the mountains

On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows,

In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame,

The good deeds a man has done before defend him (verse 97)

Oppenheimer believed that like Arjuna, the warrior Prince, and Orwell, the police officer, Oppenheimer was following the Dharma of a scientist but Oppenheimer very soon realised that his and his team’s work had resulted in the creation of one of the most powerful weapons, which if used would lead to the destruction of countless number of living creatures and the land in and around them. Will I be able to convince others, but most importantly to my moral self, that my decision and actions were justified, he could have asked. Maybe he was looking for some consolation, a semblance of which he could have found in one of the Sanskrit verses in the book Nītiśataka (see above).

In Sanskrit the verse reads:

वने रणे शत्रुजलाग्निमध्ये, महाण्वे पर्वतमस्तके वा।

सुप्तं प्रमत्त विषमस्थित वा रक्षन्ति पुण्यानि पुराकृतानि

The English translation of the Sanskrit verse that Oppenheimer remembered and quoted is good, and I like it, but it has a few extra or unnecessary words. For example the Sanskrit original doesn’t mention the metaphor of ‘the dark great sea’.

It’s more accurate, although less poetic translation will be:

In the forest, in the battle-field, in the midst of enemies, or waters, or fire, or on the top of the mountain or

whether one is sleeping, or intoxicated, or in any danger, the meritorious actions of the past alone protect a man.

Oppenheimer hoped that he would be able to count on the good deeds he had done earlier or would do later in his life might protect him and his name, and thereby bring him solace.

Most religions consider human beings as sacred and therefore violence against them and killing them is not only a crime and a sin, but an evil act. I, however, prefer secular reading of the notion of sacredness of human beings as proposed by Raimond Gaita who replaces it with the idea of the ‘inalienable preciousness of human beings’. To deny this value, and to act in ways which doesn’t cherish it, opens means to transgress their rights as human beings both in times of peace but more so in times of armed conflicts and war, even when they are waged as self defence or to protect our values such as freedom and equality.

The word Ahimsa appears only four times in The Bhagavad Gita but the scripture is often invoked in defence of the practice of Ahimsa or non-violence in personal, social, political, and cultural life. The verses dealing with Krishna urging Arjuna to fight and kill are interpreted in support of moral courage to engage in war that is deemed just no matter how much destruction it might bring about.

Oppenheimer apprehended this soon after the so-called ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He did believe that he had blood on his hands but in an interview in July 1965, available in the archives of CBS, shows his ambivalence, his regrets and hopes, both as a scientist and as a responsible human being. I admire his courage and candour and the calmness with which he expresses his opinion.

I urge you to watch and listen to the interview and make up your own mind.

Note

The essay ‘George Orwell’s Elephant’ opens my book George Orwell’s Elephant and other essays, Sydney: Gazebo books, 2024

References and other material used

Debjani Ganguly, ‘Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds’ – the Bhagavad Gita explained'.’ The Conversations, October 25, 2023.

Moreshvar Ramchandra Kāle (1902), The Nîtiśataka and Vairâgyaśataka. Reprinted as Nīti and Vairāgya Śatakas of Bhartṛhari, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1902 (Brief commentary in Sanskrit, translation and notes in English).

Raimond Gaita, A Common Humanity: Thinking about Love & Truth & Justice, Melbourne: Text Publishing, 1999.

Robert J. Stephens, ‘What the ancient Indian tex Bhagavad Gita can teach about not putting too much of our identity and emotions into our work'.’ The Conversations, February 27, 2024.

Vrinda Nabar and Shanta Tumkur, The Bhagavad Gita, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997 (English translation).